Alberta M.C. Spreafico

January 24, 2021 · 8 min read

Ex Novo – Science behind the scenes

“Ex Novo – Science behind the scenes” is a series of articles born within ISA’s blog in collaboration with the Collegio Nuovo – Fondazione Sandra e Enea Mattei in Pavia, whose students community is marked by a strong presence of women in science. Science is research, long hours to carry out experiments in the laboratory or in the field, but science is also communication, grant writing, entrepreneurship, administration, teaching, project management, leadership and many other facets. We will post articles, interviews and short stories on these multiple aspects of the scientific endeavour. Should you like to contribute with your experience, do not hesitate to get in touch with Michela, ISA’s Head and Collegio Nuovo Alumna, here: michela.bertero@crg.eu.

A systemic approach to healthcare innovation

As a researcher in development economics, I always felt that research without practice remained limited in its potential to innovate and make a difference for human beings and societies. On the other hand, working on-field in international development projects, I realized that practice without theory missed out on empowering “tools”. Aligning the two throughout my professional life, made all the difference.

When I joined a group of medical doctors working on healthcare development programs in (so-called) developing countries, our mission was to integrate point-of-care ultrasound and tele-medicine capabilities to enhance healthcare accessibility, quality and sustainability. The same innovations had proved effective to support astronauts on the space station, and the United States’ National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) had turned to us at The Henry Ford Innovation Institute, in partnership with a scientific society (The World Interactive Network Focused On Critical UltraSound, WINFOCUS), to build upon them to enhance care on earth.

However, it soon became apparent that providing technology would not per se make the desired difference. On the contrary, it may even disrupt processes in an unsustainable way, generating needs that could not be met in the long-term.

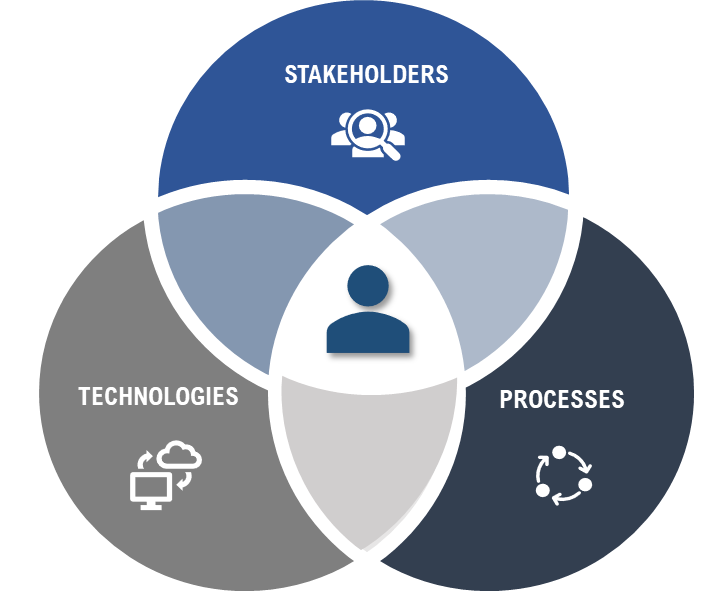

The research I had carried out on understanding and assessing development from a person-centric, multidimensional, systemic and context-specific perspective proved helpful. Indeed, the healthcare development programs called for an intrinsically multidimensional and systemic approach that could be context-specific and evidence-based, introducing innovation across three interrelated macro-categories (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Three key macro-categories for effective innovation: stakeholders, processes and technologies.

First and foremost, stakeholders – people potentially impacted by the innovation – needed to be identified, involved, their needs heard and taken into account, and their competences enhanced. It was essential that the project’s goals were aligned with stakeholders’ needs, that the innovations were of value to them and that they became co-designers and motivated “champions” of the initiative.

Typical stakeholders we collaborated with ranged from policy makers (such as, Ministries of Health), managers (as hospital directors), healthcare providers (as medical doctors, nurses and community health agents), patients and caregivers, as well as manufacturers (as technology providers).

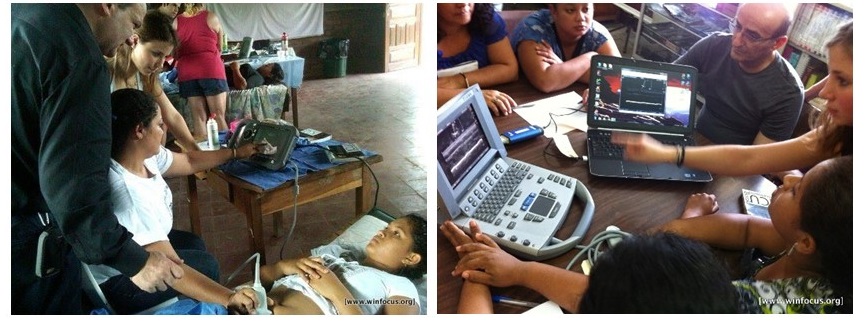

Stakeholders’ lack of competences can be a significant barrier to innovation. Hence, a fundamental component of our development program was providing tailored interdisciplinary training (Fig. 2). Empowering stakeholders with adequate competences, especially in the medical field, entailed developing tailored clinical, technological, and socio-economic education modules. Diverse capabilities and regulations, required having specific training modules for patients and caregivers, for community agents, for nurses and for medical doctors, as well as powerful toolkits for policy-makers and managers. For example, nurses were taught to capture images and identify a possible at-risk or pathological condition, while tele-ultrasound allowed them to connect remotely to the Medical Doctor of reference for a second opinion; Medical Doctors, on the other hand, were empowered in performing diagnosis and clinical decision-making processes. Multiple training modules were organized, competences tested, and providers certified.

We also collaborated with manufacturers to integrate just-in-time guidance (such as, 3D visual guides accessible on demand through the ultrasound machine, that would guide the providers towards an accurate use), as well as long-term remote training and support capabilities.

Figure 2. Point-of-care ultrasound and tele-ultrasound training sessions for nurses in rural Nicaragua.

Further, since at the heart of our initiatives was the goal of lasting innovation and empowerment, we collaborated with medical schools to integrate our curricula modules within undergraduate education – contributing to empowering future healthcare providers. This long-term vision proved of value also in Italy, where, in partnership with the Collegio Nuovo and the University of Pavia we integrated a module dedicated to point-of-care ultrasound within the undergraduate curricula.

Secondly, for innovations to be sustainable in the long-run and impact a broad range of people, they must be integrated within context-specific systemic processes and norms.

This entailed working to tailor projects to the specific local healthcare system; integrating innovation to virtually connect and enhance communication across the healthcare referral chain from remote primary healthcare posts to secondary and tertiary hospitals of reference; or connecting mobile clinics to community care health posts – favoring the creation of a patient-centered, connected healthcare ecosystem.

It also meant identifying and innovating the norms and scientific guidelines that regulated the use of certain medical technologies within the medical practice. Indeed, digital health innovations often require for a medical innovation first. Only through evidence-based innovation, can stakeholders be enabled to adequately utilize certain digital health innovations and their use legitimated and reimbursed within the National Healthcare System or by insurance providers. In order to support the evidence-based innovation of governance, we initiated a rigorous scientific process of international consensus conferences that validated the clinical safety, effectiveness and value of novel uses of point-of-care ultrasound. On this basis, scientific evidence was able to foster an evidence-based cultural innovation, that allowed medical doctors to be committed and it enabled the redesign and enhancement of patient pathways alongside normative adjustments.

Finally, technology. The general prerequisite is selecting “the right technology, for the right context and the right user”. For example, in the case of ultrasound machines to enable point-of-care diagnostics integrated with remote tele-medicine capabilities, the machine most adequate to use in mobile clinics was very different from the one required in the tertiary hospital of reference. Similarly, the means through which to provide tele-medicine capabilities through internet connectivity differed – ranging from having to set-up radio waves and rely on satellite systems, to using SIM cards and Wi-Fi capabilities, or having the possibility to use Ethernet. This entailed deeply understanding the context and the users to assure effective and long-term technology use, as well as working with manufacturers to innovate and provide adequate and differentiated technological capabilities, and with policymakers to innovate procurement procedures.

Interoperability of data systems is another key aspect. Interoperability allowed the transmission of ultrasound images and patient data, through secured systems and in respect of patient privacy, allowing for the empowering impact of tele-medicine. Interoperability is also fundamental as it allows integrating patient data derived from multiple sources, providing a holistic patient profile and allowing, in turn, for more effective and personalized clinical management. Guaranteeing interoperability and usable patient data then paves the way to the vast potential of machine learning and AI capabilities. Nowadays, cloud platforms can greatly support interoperability of healthcare data and its transformation into actionable insights.

Figure 3. Robust, water-proof portable ultrasound machine, adequate for use in rural contexts and mobile clinics.

It was through this inherently multidimensional, context-specific and stakeholders’ engagement-driven approach and a 360° vision that we were able to integrate innovations that increased accessibility, quality and sustainability of care, all the while empowering healthcare personnel and patients, across different healthcare systems, providing a lasting positive impact in multiple countries. Pilot project, as well as more extensive systemic innovation endeavors, were carried out in Brazil, Nicaragua, India, China, Lesotho, Mozambique, amongst others.

While the experience within these development projects has been significant per se, I still turn to it today, working in Italy as a healthcare and pharma consultant on digital health innovations. I do so, evermore, right now – while amidst the dramatic global COVID-19 pandemic crisis, stakeholders increasingly turn to digital health solutions to ensure continuity of care and enhancement of primary care, while reducing hospital visits.

In Italy, as worldwide, the demand for digital health solutions, especially for telemedicine applications, has had an unprecedented acceleration. From 2014 to 2017, the Italian National Institute of Health (Istituto Superiore di Sanità, ISS) mapped approximately 350 sporadic telemedicine initiatives; conversely, during just the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, from mid-April to mid-June 2020, there were over 174 experiences [1] – increasingly targeting not only COVID-19 patients, but also chronic patients in need of long-term care.

However, with technology alone, it would be difficult to imagine a lasting difference and a scale-up of a long-needed digital health transformation beyond the pandemic period. What provides the basis to believe that the “new normal” will also entail a somewhat more digital healthcare system, is an ongoing, incremental process of multidimensional innovation.

A cultural change is starting to emerge across stakeholders – especially with regards to telemedicine capabilities: citizens and patients are witnessing the actual need for digitally-enhanced care; healthcare providers are increasingly recognizing its potential, if adequately integrated within patient pathways, and they are fulfilling research to ascertain its clinical effectiveness; and policy-makers are modifying norms so to provide for reimbursement within regional healthcare systems, acknowledging its need to fortify primary care and enable a connected healthcare model. There is also the intention to prioritize funding for digitalization and health innovations within the framework of the Next Generation Europe recovery fund.

Recent data, following the start of the pandemic, sees 95% of General Practitioners being in favor of using telemedicine, 70% of Specialists and one out of three citizens wanting to try a tele-visit with their general practitioner [2]. The PubMed database testifies to a spike of publications related to telemedicine in 2020 (+ 39% vs. a compound annual increase in the last 10 years of +16%). Coherently, from a governance perspective, while the reference for telemedicine use in Italy had long been the Telemedicine Indications written in 2012 and published in 2014, a vibrant normative evolution is ongoing and updated indications have recently been approved, allowing for the reimbursement of certain forms of telemedicine within the National Health System (NHS).

However, a further and lasting scale-up, that goes beyond the needs generated by the pandemic, will require adopting this kind of multidimensional systemic approach. It is the time to engage and empower stakeholders, to implement pilot projects of digitally-enhanced patient journeys along the

NHS, to evaluate their multidimensional impact and shape norms that are supportive of value-generating innovation, while always guaranteeing safety and data-privacy. With this sort of commitment, we can emerge from the tragedy of this global pandemic with the concrete mission of enhancing healthcare accessibility, quality and sustainability, also through a digital health transformation.

[1] Alta Scuola di Economia e Management dei Sistemi Sanitari (ALTEMS) Instant Reports, 2020

[2] Osservatorio Innovazione Digitale in Sanità del Politecnico, 2020, on a sample of 740 General Practitioners and 1458 Specialists