Gabrielle Bertier and Michela Bertero

July 16, 2021 · 8 min read

For the series “ISA 10 years”, Michela interviewed Gabrielle Bertier, one of the first people to join ISA already back in 2010!

You were one of the first members of the International and Scientific Affairs team at the Centre for Genomic Regulation, back in 2010. It was actually called ICSO, International Collaboration and Sponsorship Office. What led you to apply for a scientific project manager position? Do you still remember the first days?

Ever since high school, I was always interested in how science, and particularly biology, impacts society. Back in 2010, I had just graduated from my master’s, and in the last semester, I had completed an internship in Dr. Anne Cambon Thomsen’s interdisciplinary research team at Inserm in Toulouse. Anthropologists, philosophers and legal scholars worked hand in hand with geneticists, medical doctors and epidemiologists to tackle ethical, legal and social issues (ELSI) linked with advances in biology and medicine. I had enjoyed the environment, and the type of work so much that I knew I wanted to continue to tackle these complex and impactful issues, even if I was not sure being a researcher was for me… so when Anne asked me what I wanted to do next, I told her “well, I’d love to learn Spanish!”. She said she was involved in a recently funded European research project on genomics, GEUVADIS, which was led by a researcher based in Spain, Dr. Xavier Estivill, and that they may be looking for a project manager. That is how I ended up applying for the job at the CRG. Even though I was very passionate about genetics, and more precisely genomic ELSI, I honestly had only a rough understanding of what project management actually entailed, and overall felt that I knew very little about anything. But I was up for the challenge! I was in complete awe when I heard I actually got the job. I remember the first days, I had this feeling of incredible privilege and pride. Walking around the CRG building, meeting super smart and passionate people, learning so much about science, about the project, and about scientific project management, and also catching a glimpse of the jaw dropping beach view every time I stepped on the 5th floor terrace! I really felt like I had been given the opportunity to take part in a critical mission: supporting researchers realizing their goals, to better understand biology, and ultimately positively impact patients’ lives, and society at large. I was exalted! Plus, I got exposed not only to Spanish, but also to Catalan, and the diverse cultures of Barcelona, and discovered my now absolute favourite artist: Joan Miró.

Figure 1. View of Barcelona from Fundació Joan Miró, 2012

And so you started. What were the main lessons you learnt at ISA?

Since this was my first real full-time job, I learned everything about what it means to be a professional scientific project manager – from how to manage deliverables, budgets and people, to the organization of scientific events, and the importance of having a good understanding of the science to provide efficient management support to researchers.

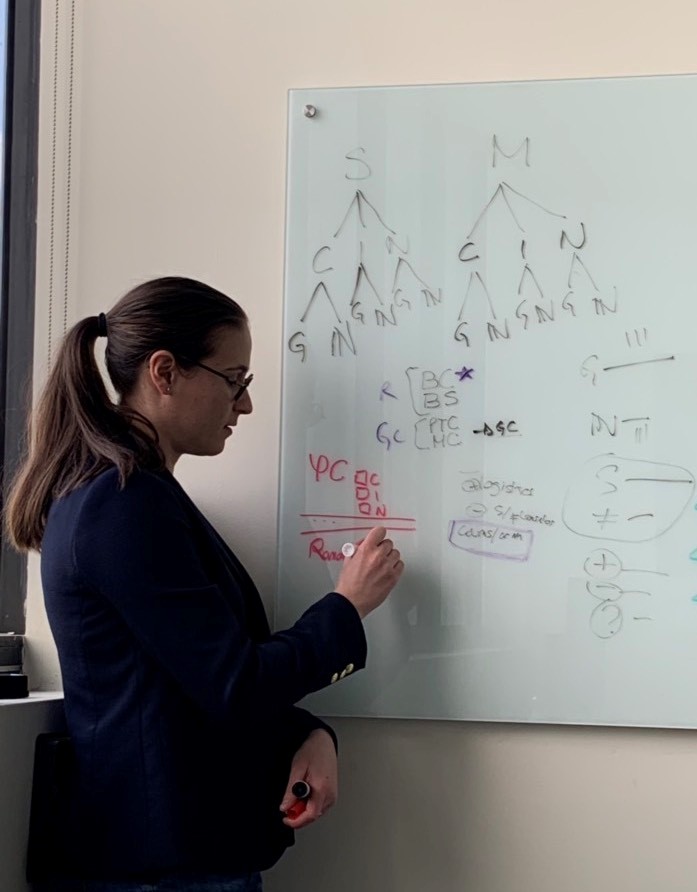

Figure 2. One of Gabrielle´s successfully organized meetings.

I also learned about the joys and pains of scientific grant writing, and how to understand the cryptic language of EU calls for proposals. You, Michela, were incredible at teaching me the delicate art of crafting ambitious research proposals that balance a Principal Investigator’s scientific goals with those of funders like the European Commission. More generally, I learned how to communicate about complex scientific issues in a way that is understandable for the general public, which is an important life skill I have been using ever since. Another valuable lesson was learning how to prioritize, when everything seems critical and you do not have enough time to handle all of it at once… and not getting overwhelmed when hundreds of emails pour in every day in an uninterrupted flow. It may seem trivial, but this was an important crash course in efficient email filtering, too!

Probably you also had some experiences that were not so pleasant…

One of the toughest lessons I learned was that the combination of being young, being a woman and not having the three letters next to your name – Ph.D. – sometimes meant not being recognized as someone who can contribute actual ideas to a project. I still cringe at the thought of this one researcher asking me to handle his luggage after arriving late at a conference I had helped putting together, just 10 minutes before I was due to present to the entire audience… I learned that even when you have a clear role within a project, respect is not a given, but it is something that you have to work hard to earn, and it is a more arduous path for some. Thankfully, many others had a different attitude, and the most powerful recognition of my contribution as a scientific project manager was when the lead postdoctoral researcher decided to add me to the authors list on the main project article, which ended up being published in Nature. I still remember the feeling of seeing my name alongside those of incredible scientists who had participated in the research. Explaining her draft author list to everyone on the conference call she said: “I put in everyone who was consistently present on our weekly calls, and contributed in one way or another to the success of our collaborative effort.” More than the publication itself, her recognition of my work, coming from a scientist I greatly admired, made all the hard work worth it. Earning her respect was a defining experience, not only because it made me realize that my work was being noticed, and considered important, but also because she is someone who I was not afraid to call for career advice years later.

Maybe the most important lesson of all was that everyone you work with will teach you something… intentionally or not! Learning about what not to do is just as important as having positive and inspiring examples above and around you.

After your time at the CRG, you moved on to start your PhD in Canada. It is an unusual path to go from project management to academia – often it is the other way around. What was it like, and how did your experience as project manager impact how you approached your PhD?

I firmly believe my experience in project management helped me tremendously in my PhD. First of all, I had very clear motivations and objectives going in: I had taken the time to think of a subject I was truly passionate about – the integration of genomics into clinical care -, I had chosen two amazing labs, in Toulouse and Montreal, and was lucky to have two highly regarded professors agree to supervise me – Anne Cambon Thomsen was one, and the other was Yann Joly, Professor at the Center of Genomics and Policy at McGill. Both Anne and Yann also helped me be fully funded for my PhD, which meant that I could focus 100% of my time on my research, which is an incredible privilege. The grant writing experience I gained at the CRG definitely came in handy when trying to get funded for my own project! Overall, the maturity I gained by working for four years was essential, because it helped me see the bigger picture and not get bogged down by the hurdles I encountered along the way.

I basically conducted my PhD just like the scientific projects I had managed before… except this time I was doing the work on top of managing it, which had its challenges but also meant I could make up a lot of the rules. Of course, I was guided by university program obligations, but I set a very strict deadline for myself, which was four years. I knew the importance of setting clear deliverables, budgets and timelines. Because I had been in the academic world for a few years, I also knew very well how competitive it was, and was able to keep a level head when my papers were rejected or when I was not selected for an award or a fellowship. Mind you, rejection was not fun for me either, but I never really lost the drive to reapply, or resubmit my papers elsewhere. Another unexpected advantage I had as a scientific project manager is that I was used to dealing with bureaucracy, and sometimes frustratingly complex and lengthy administrative processes. That also helped me a great deal when trying to combine the requirements of both universities I was affiliated to in order to get my degree.

What was your challenging moment during the PhD?

After being a manager for a few years, where most days filled up with tasks that had to be completed relatively rapidly, what attracted me in doing the PhD was giving my brain the opportunity to zoom out and focus for longer periods of time on a smaller volume of issues and questions. There is one thing I was not prepared for however… which is the blank page syndrome. For a good month, I got completely stuck, unable to think of what to do next, and how to approach the next step of my research. In hindsight, that did not last long, but at the time I remember feeling quite panicky. Thankfully, I had the support of my friends from the PhD program, some of whom were painfully familiar with this problem, and once again, my supervisors came to the rescue and helped me move forward. Having experienced these two widely different paces of work helped me tremendously because it allowed me to find the sweet spot at which I am happiest, most creative and most efficient.

Figure 3. Gabrielle with her parents at her PhD graduation, 2019.

After the PhD you started working in the USA. By then you had already worked in France, Singapore, Spain, and Canada. What can you tell us about the value, and challenges of these international experiences?

One challenge that tends to be underestimated is the one of obtaining visas. Because I have moved around a few times, I always think I know what I am in for, but things consistently go wrong, and become extremely stressful and complex. In a way, as a western European, I think I hold on to an idealistic view of the world, where crossing borders is easy, fast and commonplace, but needless to say, reality is very different. Looking for jobs internationally is a humbling experience, because previous knowledge accumulated for one country rarely applies elsewhere.

On the positive side though, once the visa is in your hand, having the chance to be exposed to different work cultures is an incredible privilege. It helps enrich your worldview and become more tolerant to different approaches, and ways of thinking. There is a large body of evidence showing the advantages of having a diverse team – made of a variety of genders, cultural, educational and disciplinary backgrounds – tackle complex issues. I believe this is true at an individual level as well.

Did anything surprise you?

One thing that I am fascinated by is how different societies and cultures perceive healthcare, and more specifically the role of Government in handling healthcare issues. Again, as a French woman, the belief that healthcare is a fundamental right, and that it is a key governmental responsibility has been so deeply ingrained in my mind that it is almost impossible to consider it otherwise. Let’s just say working in the largest hospital in New York burst that misconception wide open! What I have noticed by working in these different contexts though, is that most people’s perception is that it is better elsewhere, and the “grass is greener” phenomenon is a very real, very common occurrence in healthcare. For instance, during my PhD, I interviewed clinicians in Quebec and in France, they consistently had the firm belief that the other system was better. As someone who has experienced a few different systems, I can be in a position to propose ideas inspired by what I empirically know works well elsewhere. This is not to say I have all the answers, and quite far from it, but these international experiences have equipped me with a great list of subject matter experts in different countries and contexts to call for help and advice when I feel stuck on an issue.

You have recently made a new move to go from the academic sector to industry, what motivated this change and… are you happy you took that path?

This move was definitely not an obvious one, and I had to think long and hard before deciding to pursue a job in the for-profit world. It took some soul searching to make sure this move would help me pursue my career and life goals, and what it boiled down to was asking myself: can the search for financial profit go along with having a positive impact on patients, and society at large? In the case of the Brooklyn startup I joined in 2019, the answer was a definitive yes, and so, I took the plunge! Rather than basing my decision on the financial aspect of things, which quite frankly was rather scary – I remember the hours spent on investopedia trying to understand the terms of my contract – what attracted me was the agility, and flexibility of working in a small team. After working at a 40,000 employee strong, massively complex organization, joining a team of 4 was a breath of fresh air! I am extremely thankful to the founders for opening this door for me. As someone for whom learning new things is so important, “switching sides”, leaving academia and entering industry was the right move because it allowed me to branch out and develop a whole new skillset. It has expanded my world view tremendously, and allowed me to feel like I can have a more direct impact on the world around me.

Figure 4. Morning commute view of NYC, 2020

What would you say have been the main driving forces influencing your career decisions?

One of the key factors for me has always been to make sure that ultimately, my work can have a positive impact. As someone who has always been in the healthcare field, even though I am not trained as a healthcare professional, I think of every job opportunity with this fundamental question: down the line, would I be contributing to helping patients? And more generally, can I get behind the key mission or “raison d’être” of the organisation? If the answer is yes, then I start considering all the other questions:

- What is the learning-to-contributing ratio in that position? In other words, in order to perform well in the job, how much will I be contributing my existing skills and knowledge, vs developing new ones?

- Will I be connecting with people within and outside my team who I can learn from, and will I be exposed to highly regarded subject matter experts?

- What would my impact be on the project, team and organization?

- How will I be supported, and will I have the means and opportunity to support others in being successful at their job?

- How will this job help me get my next job?

For the curious ones, what is next bridge Gabrielle would like to cross?

That is not an easy question. I recently moved back to Montreal to join a medical artificial intelligence (AI) technology company, and I am definitely far from done learning about the benefits of applying machine learning methods to answer the toughest questions in healthcare. It is beyond exciting to be a part of this new wave of innovation. Because of my background in genomics, I am used to thinking about the clinical impact of collecting, analysing and sharing genetic data, and I am now exposed to projects dealing with a myriad of other data types, including clinical imaging, electronic health records and administrative and claims data. How we as a society deal with this exponential increase in healthcare data is a critical question for the next 5 years; and more specifically, how can we strike the right balance between protecting privacy and unlocking the potential of this data to solve clinical questions? I do not think that fully answers your question, but these are the types of questions I am asking myself these days. Let’s see where it takes me next!

Figure 5. Looking at clinical trial design at Mount Sinai.